Response from the Old World of Wine

This presented a sudden, unexpected challenge, which the old world of wine could not meet; established EC members had to contend with costly restrictions, whilst the oenological and viticultural technologies of newer members had become outdated. Because of these competitive disadvantages, the EU directives had to be changed in order to accommodate new methods of vineyard irrigation, and to include guidelines on chip use and winery technologies.

Only since the drastic cutting back of the guaranteed distillation system in the 90s by the EC was the old world of wine able to develop a new awareness of quality and grapevine varieties. Whilst Spanish viticulture was already able to create favourably‑priced alternatives to French wine during the 70s, Portugal lagged behind. Before the opening up of the borders, which came about thanks to the swift and decisive action by Presidents Mitterand and Kohl (Schengen Agreement, in 1986), Portugal and Spain were at a disadvantage by comparison with EEC countries, because they were not yet members, and the quota system and customs policies, as well as their own bureaucracies represented almost insurmountable trade obstacles.

This changed with the EC Association Agreement. Indeed, in the international price‑quality ranking Portugal fared quite well, thanks to shrewd Port wine policies and a handful of beverage and wine manufacturers of international repute. The quality of table wine products was producer‑dependent, and therefore very little of it was exportable.

In 1992, the Portuguese Ministry for Economy engaged the American “guru”, Professor Michael E. Porter, head of the Institute for Strategy and Competitiveness at Harvard Business School, to help dismantle the prevailing communication barriers private entrepreneurs experienced when dealing with State organisations, encourage intra‑sectoral communication, andto use the different viewpoints of the participants to focus on creating a cohesive and an economically viable wine industry. Key to the success of this initiative was that the uncritical acceptance of the State as a God‑ordained and unavoidable sovereignty was called into question, and the voice of the professional sector was then heard.

Rapidly, the existing wine regions were divided into demarcated wine regions (DO). Interprofessional commissions were created: the CVRs were made up of local producers (wine manufacturers, cooperatives, and wineries). The CVRs quickly took over the functions previously managed by officials.

Since the sales policies, and export policies in particular, of the large wine manufacturers in Portugal in the 80s were outdated and in need of reform, their co‑founding of Viniportugal, a marketing promotion association, created the opportunity for them to establish themselves on a wider scale, particularly in foreign markets. The problem was that the Ministry for Agriculture already deducted a levy to finance its viticulture‑related activities. Private wine manufacturers therefore suffered as a result, because they now had to pay a double tax.

There followed a painful process, which demanded rethinking as far as grapevine varieties and winery technologies were concerned. To solve this problem substantial resources were made available by the EU in the 90s so that the necessary winery facilities could be established.

With the Vitis programme beginning in 1997 (Decreto‑Lei N.o 83/97, of 9 April), generous concessions were awarded for new vineyard installations, as well as restoration of old ones previously stocked with the wrong grapevine varieties. Powerful clones or clone mixtures were increasingly available, so that today almost half of the Iberian Portuguese vineyards are competitive. High performing clones, or clone composites became more and more available so that today almost half of Portuguese land planted to vineyards is now competitive. The percentage of production exported quickly doubled and even expensive wines found their way abroad. Scientists, journalists and other opinion makers attended conferences and symposia in Portugal, whilst associations and companies became more active and influenced the qualitative production process in private enterprise. This precipitated huge successes with awards, and press accolades. Thus Portuguese wines, due in large part to their high quality and unconventional autochthonous grape varieties gained tentative entry to some of the target markets in the international wine trade.Last, but not least, the enormously expansive Angolan market has helped since peace was established, by purchasing the lower priced, more traditional wines from by the market.

The second “Porter Cluster” which was conducted by the Monitor Group (a Michael Porter affiliate) in 2003 (as a follow‑on from the 1992 initiative), and which focused on the market, could not achieve its objective: to coordinate public sector cooperation with the private sector objectives. In addition to the quality policy which was becoming more closely consistent with current practice, the initiative wanted to create a purely market‑ orientated plan along the lines of the Australian model, where production, science, education and marketing operate together as one cohesive approach and policy in order to bring Portugal into the modern world. To this end, a separate research and development coordinating agency, much like the Australian Grape and Wine Research and Development Corporation, was to be created in Portugal using a portion of the EU funds earmarked for science in keeping with the market

What is relevant to the subject of grapevines here is that innovation is a vitally strategic, key element in the Porter Cluster approach. Establishing pilot varieties and reducing the range of varieties was a marketing imperative. This is where the optimum grape variety plays a central role in the new world of wine: it is the variety producing good wine at low cost. The Cluster was considering this scenario with two varieties, the Touriga Nacional and the Arinto (Campaign 1). This concept in favour of a competitive, vineyard‑managed upgrading of leading grapevine varieties in conjunction with a reduction in the number of varieties so confusing to the consumer, known as “varietal rationalisation” was clearly being encouraged, but fears were already raised during the Porter Cluster workshops (Campaign 4) that this prime objective in Portugal might stand in opposition to the view of grapevine varieties as a “museum, or preserver of national heritage”, and thus possibly have to compete with continued widespread maintenance of grapevine biodiversity.

The Porter Cluster was a step in the right direction; it was a way to enable the Portugal of the old world of wine to catch up with the new world of wine. The financial crisis at the end of the first decade of the third millennium came far too early, and the level of debt of most small and medium‑ sized businesses is still too high. The goals defined by the Porter Cluster will need substantial investments and innovative thinking about grapevine variety policy.

In Spain, the new designations of origin were certainly not news of the Second Coming, as Cañin (1998: 450) cynically notes, but they issued a solid legal basis for bonafide producers and ultimately led to the “Spanish wine” model of success. Entrepreneurs like Miguel Torres, the Codorniu family with its 2,000‑hectare colonia europea viticola in Raimat, Lerida, or the owner of the Freixenet Group, Marqués de Riscal, to name but a few, have shown what good business people have to do. The old wineries, cooperatives and wine manufacturers, including many newcomers, often from the booming construction industry followed suit, thus securing the restitution of quality Spanish wine. Once again, we see the interplay of the grapevine variety with the terroir to which it is suited at the centre of a strategy which incorporates modern winemaking technology. The international launching of Spanish wines – often in need of explanation before the marketing drive – was only made possible by using the most modern viticulture techniques and cellar technology available, thus ensuring the great worldwide success they have achieved. What matters is the price‑performance ratio and the quality of the wine in the consumer’s glass.

Castilla La Mancha is a particular challenge in every respect as the largest wine growing region in Spain covering over 600,000 hectares of vineyards planted to the Airén grape variety, which only does well in this region, and yet it is the most widely planted grapevine variety in the world. This clearly demonstrates the specificity of this region. If it were taken on its own, it would be the third‑largest winegrowing country in the EU. (Francisco Sánchez Rodriques, Analisis del Paisaje Castilla La Mancha in Actas del I Encuentro de Historiadores 2000: 127 ff). After accession to the EU attempts were made to move this vast wine growing region away from the image of being a producer solely of cheap table wines and sparkling wines.

1997 saw the heavily subsidised investment into the planting of new vineyards under the quality wine varieties of D.O. Almansa, D.O. Mérida (in 1992 this D.O. covered 14,000 ha), and D.O. Jumilla (D.O. since 1975‑50,000 ha). The following D.O. varieties were then added: Modéjar (1997 D.O. – 2,100 ha), La Mancha (1997 D.O. – 178,107 ha), and Valdepeñas (1997 D.O. – 16,000 ha). The following were particularly encouraged: the Tempranillo (Cencibel) and Cabernet Sauvignon red varieties, as well as the Alicante tintorero (teinturier) in Almansa, and the white varieties of Macabeo, Chardonnay, and the Albillo in Mérida. At the same time, the area under cultivation was cut back to 100,000 hectares (the same size as the viticultural area in Germany). This has made the vineyards of La Mancha something of a rarity within the EU, and they are likely to remain so for a good while yet.

One other interesting example is that of the Rias Baixas. In 1987, 492 vintners worked on 237 hectares and produced 5,850 hectolitres, which was all consumed on the domestic market, but by 1997 over 4,000 vintners worked on 2,000 hectares and produced over 60,000 hectolitres. This trend has continued steadily until the present day. This miraculous increase can be traced back to the Albariño (Alvarinho in Portugal), which had already experienced a revival in Portugal during the 70s, but has in the meantime been largely taken over by the “galegos” (Galicians). Superior cellar technology and an optimum relationship between terroir and grapevine variety have made this wine today what some might call one of the finest white wines from the warm climatic zones. Creating new vineyards in its mountainous region is possible only through heavy earth moving, although the high price of wine is an incentive for constant expansion of cultivated areas, the development of which could well add the Verdello from Rueda as the second great white wine to the many Spanish export successes. On the solid foundation of a very long shared viticultural history as well as a uniquely broad range of grapevine varieties adapted to the diverse terroirs of the Iberian Peninsula, the Spanish and Portuguese wine sectors produce a surprising, yet authentic, multiplicity of great wines of provenance, thanks to state‑of‑the‑art viticultural and vinicultural technology. Viticulture faces challenges worldwide. Spain and Portugal have provided the answer to these challenges in the form of quality wines with a specific provenance, produced from varieties well‑adapted to terroir.

Wine manufacturers too, with their new global awareness, have pointed the way forward in terms of good environmental practices, culture, and customer proximity, as can been seen from the striking modern architectural examples at Marqués de Riscal by Frank Gehry in Spain and at the Adega Mayor by Siza Vieira in Portugal.

Both Spain and Portugal are trying to provide a viable alternative to global oenological uniformity, and will continue to do so.

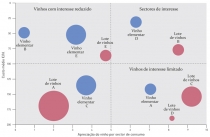

Fig. 98: In 2003 the second Consultation on Strategy with Michael Porter’s consulting 25 firm (Harvard Business School, Boston) took place in Portugal. Important issues were discussed, such as the creation of a wine marketing agency, strategies were worked out as to which grapevine varieties could produce good wines at 100 low cost (see chart above), including their promotion in the market as “pilot varieties”.

Fig. 98: In 2003 the second Consultation on Strategy with Michael Porter’s consulting 25 firm (Harvard Business School, Boston) took place in Portugal. Important issues were discussed, such as the creation of a wine marketing agency, strategies were worked out as to which grapevine varieties could produce good wines at 100 low cost (see chart above), including their promotion in the market as “pilot varieties”.