The Late Middle Ages and the Renaissance

After the fall of the Roman and Visigoth Empires, the new Islamic rulers introduced restrictions on the trade in wine, which at that time was flourishing in France and Germany. The Christian Church, with its need for sacramental wine, even outside of wine growing areas, was an important factor in this development. According to Amaral (1992: 60), “Between 630 and 647, the Bishop of Cahors, Saint Didier, sent 10 barrels of the best wine to his counterpart, the Bishop of Orleans. Theodulf, the Bishop of Orleans around the year 800, earned the nickname “pater vinearum” (Father of the Wine)”.

Charlemagne, unifier of the Kingdom of the Franks (771), was devoted to the wine trade. The famous Corton Charlemagne vineyard in Burgundy is testimony to the Crown’s interest in wine. In AD 817 in Germany, vineyards at the Abbey of Lorsch and the Monastery of Fulda were managed by the monks (Amaral, 1994: 58). Charlemagne’s son, Louis the Pious, heir to the wine growing regions along the Rhine (Treaty of Verdun 843), continued his father’s work and actively supported wine growing at these monasteries. He was buried at the Monastery of Lorsch, which was the great wine growing centre of its day. The following varieties have been documented from this time: Franken (Sylvaner), Heumisch, and Alpen (Kleinberger) (Bassermann 1907: 78).

Above all, the wine of Beaune gained high recognition in the medieval world. The closed walls encircling monastic estate vineyards became synonymous with quality. With the election and presence of the anti‑pope Clement V in 1308, these wines reached their high point in international prestige. Other major contemporary wines were the Tokaji (Tokay), and the German Johannisberger.

In the Late Middle Ages the most important technological leap towards modern wine making occurred on the Iberian Peninsula. According to Bassermann (1907: 335), Pliny had already made reference to Cato’s use of sulphur as a wine stabiliser, although no further evidence of this exists. Much later, from the records of a judgement passed in 1465 (in Cologne), it was known that the use of sulphur could lead to wine poisoning and was deemed a punishable offence. According to Ambrosi (Rühl 1995: 15), stabilising wine using sulphur was legislated for the first time in 1487. In Germany, a Reichstag edict issued in 1497 declared that “Vina quo casu sulphuraria liceat [“in which case sulphur wine is lawful”], thereby regulating the use of sulphur in wine in limited quantities, and gave details of precise technical specifications. The preservative effect of sulphur is the ingredient to which single variety wines owe their characteristic aroma. It replaced the traditional methods of preparing wine in those days using chemical preservatives (some of which were poisonous), leather vessels, enormous admixtures of honey, or concentrating must by evaporation (Diócorides and Galeno, as cited by Bassermann, 1907: 318), smoking in special chambers (the Roman fuminarium), addition of alcohol, resin (retsina) and Apotheka (Greek, Columella, I, 6, 29), all of which, as did the famous artemisia absinthium, completely adulterated the taste.

With the use of sulphur one could recognise the quality wine varieties in today’s sense of the term and thus the modern “Vitis vinifera gene pool” began to distinguish itself in terms of taste to a greater degree.

Of particular importance for the development of viniculture were the Benedictine and the Cistercian Monks, as well as certain bishops in larger cities. The selection of grapevine varieties gave birth to the great Central European varieties such as Spätburgunder, Riesling, Cabernet and Traminer.The wine had a sacred purpose as communion wine and has been dignified accordingly in literature and art.

Because a large part of the population was made up of Mozarabs and Jews, wine growing survived and so, despite the Arab occupation, did the autochtonous grapevine varieties.Even at that time Alonso de Herrera (1513) spoke of the Torrentés variety.

Rumour had it that the Pedro Ximénez variety was brought here from Germany by a German called Peter Siemens in the 16th century, which must have been a misunderstanding because the heliothermic requirements of this variety could hardly have existed at latitude 48° N.

In Portugal, it was late in the 12th century that after establishing 120 convents the Cistercians essentially became the keepers of agricultural knowledge but also provided training on how to grow wine to the faithful congregations. Through them the first quality varieties were selected and intentionally propagated. The Alcobaça Convent is one such example.

Initially, however, Portugal did not participate in this huge international revival by reason of the Islamic occupation. Since viniculture did indeed survive, it would appear that although the new rulers did not prohibit wine growing, they did not permit trade in wine, still less export trade. For this reason the Portuguese wine sector only made its appearance on the international scene much later, without ever having lost its relative standing in the domestic agricultural sector.

By the late 12th century, the Cistercian Order had grown to 129 convents across the Iberian Peninsula. As a result, viniculture and cellar technology experienced a noticeable revival, of which Alcobaça is one example. This was achieved through research and vocational training of the faithful congregation. Regrettably, the paper presented by Barbosa (1994) on this subject at the ISA Conference entitled, “Viniculture and wine in the economic context of the Alcobaça Monastery” has not been published and exists only in summary form in the conference proceedings.

From a cultural perspective, Portugal was no different from other European countries. The grapevine and the vine leaf, more elegant that those of other plants and possessing a form considered classical by the Ancient Greeks, is found everywhere on decorative ornaments in the 12th century.It achieved even greater heights in Gothic art than the peak it experienced in Roman art.

The vine and its leaves were the most dominant floral motif in the Middle Ages.Brought from the Orient, the vine achieved almost national symbolic status in Gaul, and influenced sculpture too. (Darcheville, 1998: 26). What is more, wine acquired spiritual properties because of its association with Jesus Christ. God is the vine grower, and his Son the true vine; His followers are likened to the vineyard bearing fruit, whilst His blood is symbolically represented by wine in Holy Communion.

Portugal’s long standing relationship with England has always been founded on the principle of protecting each country’s political and economic interests with regard to its neighbours. The marriage in 1387 of King John I of Portugal to Philippa of Lancaster, daughter of John of Gaunt, first Duke of Lancaster (England), sealed the Anglo‑ Portuguese Alliance. Prior to this, the relationship had involved logistical help, such as the provision of crossbows (whose arrows pierced metal armour) which ensured Portugal’s decisive victory in the Battle of Aljubarrota (against the Crown of Castile) in 1385, formalised by the Treaty of Windsor in 1386. Before this new phase of treaty making, Bordeaux wine dominated the English market. Amaral (1994: 65) recounts that “in 1308‑1309 Bordeaux exported 924,000 hectolitres, and the annual average at the beginning of the century was well over 750,000 hl!”. With the marriage of Eleanor of Aquitaine to Henry II of England in 1152, the Bordeaux vineyards fell to the English crown, a privilege which it enjoyed until the end of the Hundred Years’ War in 1453.

With this new alliance, Portugal intensified wine exports to England, and much later to colonial America. In the third quarter of the 14th century Portuguese wine was traded with the Hanseatic League, which took it to Germany, the Netherlands, Ireland and the Baltic States. Wine was transported in vats, casks, barriques, barrels, and amphorae (Marques, 1993: 82‑84).

French viniculture

The Hundred Years’ War (1337‑1453) wreaked havoc on French viniculture, and the French lost a substantial part of the English wine market. With the end of the war, and the consequent reversion of Aquitaine to the French crown and the Turkish occupation of the Mediterranean islands England was cut off from its former procurement markets. This facilitated the entry of Iberian, but particularly Portuguese, wine into English and international trade. From 1360 onwards, England encouraged the importation of Portuguese wine, not so much the light table wines, which in spite of the situation continued to come from France (Bordeaux until 1460) and Germany, but rather the dessert wines, particularly those made from the well known Malvasia and Muscatel grape. These varieties doubtlessly belong to the Vitis occidentalis gene pool. They were previously known as “Greek wines” and were traded by Venetian merchants before the Portuguese took over. In England, they were thought of as Malvasia (Malmsey) or Romanian wines, and it is possible that Malvasia‑type wines began to come from Portuguese vineyards as well (Zurara, 1915: 73).

IN PORTUGAL

Lisbon: the first Portuguese export successes were the wine from the Monção area (vinho verde), and the “Osoye” and “Bastardo” dessert wines. At that time, one did not speak of “Muscatel from Setúbal”, although this has to be what was referred to as Osoye. Johnson (1990: 166) writes, “… It began with the sale of wine from the North; in 1430 primarily because Lisbon was an important port of embarkation, “Osoye” gained more widespread recognition, as did Bastardo later”. Johnson (ibid.) continues, “There is no doubt about the Osoye of the 14th century; it was the dessert wine from Azóia, a small harbour situated on the South bank of the Tagus, quite close to Setúbal.” Marques (1992: 83) gives the following names by which Osoye was also known: Ansoye, Azoy, Asoy or Azoie. Kuske (in Marques 1992: 83) writes, “Ansoye is a wine that is made from dried grapes, or even those of bastardo, so called because of its uncertain colouring”. (Dion, 1959: 321‑322) refers to it as “a small harbour situated on the south bank ofthe Tagus, near Setúbal” (Johnson 1990: 166). Franco (1938: 6) writes, “The wines from this area were famous because of their excellent quality which made them particularly rich and noble wines”. Statements such as these lead one to assume that these wines are the same as those that the Phoenicians first brought to Alexandria (Egypt) and Kelibia (Tunisia), and probably to Setúbal too, which would give them the characteristics of the so‑called Greek wines.

Although these vineyards were destroyed in the 12th century by the Almohad (Yaqub al‑Mansur), viticulture recovered and soon thereafter produced exceptional wine which was in great demand, as Franco (1938: 7) discovered.

During the reign of Manuel I, the vine was an important ornament. Thus we find, amongst others, the Ermida de São Pedro da Ribeira [Chapel of St. Peter at the Riverside] in Montemor‑o‑Novo has a border of vines painted on the apse which dates back to 1511. It provides really interesting evidence of the wealth of grapevine varieties available at the time. Jorge Muchagato (1994) has detailed numerous examples of this in his valuable work on the depiction of the grapevine in Manueline achitecture.

The extra duty imposed in 1693 on French wines during the reign of William III resulted in the English merchants further intensifying their interests in Portuguese wines. In 1703, English interests in Portugal were cemented with the Methuen Treaty (which entailed Portugal neglecting its own textile sector in favour of exporting wine at a low level of duty to England, in return for England’s woollen cloth exports attracting no duty in Portugal.) Hundreds of thousands of hectares of new vineyards were planted, for the most part in the Alentejo. (In the event, the English kept the agreement for a short period only.)

At the end of the Middle Ages, Portugal had the largest trade fleet of the then known world. It carried spices, silk and porcelain ware as far as Japan (see Fig. 65, Namban Folding Screen [Namban Byobu]); and transported slaves from Africa to Brazil, so that Portugal could exploit its gold and mineral wealth. Documents even exist on the piracy of Portuguese wine during this period. Marques (1992: 84) writes, “Portuguese wine destined for Germany was definitely seized by English pirates from Sandwich”. The punitive expedition of 1471, which King Afonso V had entrusted to the future Marquis of Montemor, was cancelled because of the death of the English King Henry VI, suspected to have been caused by the corsair Focumbridge, who was in his service (Fonseca, 2010: 29).

The stability of the genetic base of Portuguese and Spanish grapevine varieties was one interesting phenomenon.They retained their “endemic” individual characteristics, which were fortified by new varieties introduced by migrating peoples, and by trade relations with colonising nations such as the Phoenicians, Romans and Greeks, and later, the Spanish Hapsburgs.

After Lisbon, the Algarve was one of the most important wine export centres in the 15th century. The wines of the Alentejo were shipped via the River Guadiana from the old Roman river port at Mértola to the Algarve from where they were then marketed

Documents exist on the first wine export in 1456 from Madeira to England. Johnson (1999: 245) quotes António Cordeiro (1717: 79) in this regard. In his True History (1557), the German mercenary soldier in the service of the Portuguese, Hans Standen, refers to its two main products: wine and sugar cane. In 1578, Duarte Lopez described wine production as Madeira’s most important export, and the French Consul in 1669 described it as the island’s most important source of revenue (A. Vieira, 2002: 1089). The marriage of Charles II of England to Catherine of Braganza and Cromwell’s war against Spain were two factors which made this Portuguese archipelago the focus of English military interest.The following is an exact transcription of what appears in an ordinance issued in 1665 by the English King, “Wines of the growth of Maderas, the Western Islands or Azores, may be carried from thence to any of the lands, islands, plantatinos & colonies, territories or places to this majesty belonging, in Asia, Africa, or America, in english built ships.” (A. Vieira, 2002: 1091).

By improving the competitive position of Madeira wines, made possible by using “Greek” grapevine varieties, “Malmsey” (Malvasia/Malvasier) became a favourite of the English.King Afonso V was far‑sighted enough to send for plants from Candia (Crete), including the Malvasia grapevine (Cordeiro 1717: 79). Strategically, Madeira gained in importance, because it was able to compensate for supply shortfalls of “Greek wine” from elsewhere.This was to Spain and Portugal’s advantagewhen Crete was occupied by the Ottoman Turks in the 15th century. Crete experienced a similar exodus with Muslim occupation as had Iberia, but this time it benefited the Iberian wine regions. That Iberia rose to become a wine superpower by supplying products comparable to “Greek wine” was thanks to the Venetian merchants, who had already secured its excellent international reputation. The Fall of Constantinople in 1453, which represented a victory for the Ottoman Sultan Mehmed II as did his subsequent conquest of the Balkans, caused the collapse of the local wine industry, including the marketing and distribution of its wine by a Venetian Doge. This opened up a new and important market segment for Iberian wine growers who, in contrast to the French and Germans, were capable of producing naturally sweet dessert wines. The Muscatel dessert wines from Osoye, the Port, Madeira, and Pico wines, Sherry, and Malaga and Tarrragona dessert wines targeted this all‑important new market for “Greek wines” in Northern Europe, from which the Venetians had been expelled. The centuries of Ottoman rule prevented the resurgence of original “Greek wine” in the market. It also lost its prominence because the market had developed a taste for lighter wines as processing and preservation techniques improved.

Even Shakespeare gave voice to the reputation of Madeira wines: In Richard III, when Richard sentences to death the Duke of Clarence, brother of Edward IV, by having him drowned in a butt of Malmsey. He also mentions Portuguese wine again in Henry IV when Falstaff is censured for having sold his soul to the Devil for a cup of Madeira wine.

English influence increased after the rule of the Spanish Kings Philip II and Philip III, and after the restoration of Portugal’s independence , “… The relations with the English were, however, so one‑sided that they soon engendered a feeling of apprehension” (Johnson, 1999: 220). After the marriage of the English King Charles II to Catherine of Braganza, “Bombay, Tangier and the port of Galle in Ceylon constituted her more than generous dowry” (Johnson, ibid.).

“It was easy to distinguish between table wines and the Malvasia‑based wines. (…) Of the dry wines, ‘Sercial’ was the best (amongst the best sweet and dry wines were those produced from the grapes of the ‘Bual’ or ‘Boguale’ variety, which had a spicy taste); then there are the ‘Verdelho’ grapes (also called Vidonia at the time), which proved to be a most harmonious wine. Another very good wine has been produced by blending the Malvasia with a variety called ‘Terrantez’. The simple table wines were made with a variety called ‘Tinta’” (Johnson, 1999: 247).

With the seafaring of the 18th and 19th century, nations with colonial interest such as the English, Dutch, Portuguese and Spanish were obliged to stop over on their intercontinental voyages at the Iberian archipelago. After the Treaty of Utrecht established in 1713, the Portuguese archipelago had already acquired such a reputation that its wines were loaded in favour of those of the Canary Islands (belonging to Spain), which put Spain in a difficult economic position because her wine sales suffered (A. Vieira: 1091). Even in America, correspondence dated May 1759 between George Washington and John Adams reveals an appreciation of the qualities of Madeira wine (A. Vieira: 1101).

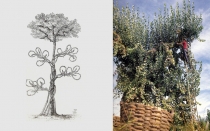

Viana de Castelo. There have been vineyards in Minho for over two thousand years. Because of its distance from the centre of Arab power, when Afonso Henriques founded the state of Portugal he could see extensive vineyard views in his home country. The wine was characterized by its mild alcoholic content and freshness, and was normally drunk during the year following production because it was not suitable for storage. Cultivated by growing the vine on trees as did the Romans (the arbustrum method. See Figs. 69a and 69b) – as is still the case today in some areas, incidentally – is what naturally gives this wine its low alcohol content at full maturity, and is the determining characteristic of this type of wine which is seldom found today.Because of its special geographical location Viana was a major exporting seaport. History tells us that the harbour was used by the first English traders to establish foreign branches. “The English installed themselves in Portugal with a huge number of special rights, and it was therefore only natural during their war with France that they obtained their wine from Portugal.” (Johnson, 1999: 221).

“During the decade following 1660, there were three English factories in Portugal: the ‘feitorias’ (or “trading posts”) in Lisbon, Porto, and Viana (…) In Viana bacalhau (dried cod) was exchanged for red wine, which was taken to England. (…) the better white wine, no doubt the Alvarinho, was traded in Monção.” (Johnson, 1999: 221)

Port wine

Prehistoric symbols found in the Valley of Foz Côa are indicative of Palaeolithic settlement. Viticulture existed in the Douro Valley before the Romans. Roman wine presses cut out of rock can still be seen today. Thirteenth century documents attest to “Riba Douro” wines. The wines were shipped along the Douro and offloaded at the ports of Porto and Gaia, where they were distributed by traders, amongst whom Afonso Martins Alho was the first on record. These special circumstances were created because the wine regions further up the Douro were inaccessible to traders, and led to problems once the British took over a substantial part of the market. Sebastião José de Carvalho e Melo, Marquis of Pombal was outraged by the one‑ sided policies of the English.He wrote, “…the English from Porto were about to destroy the most important quality grapevine varieties on the Douro and their harvests; they forced the prices down to such an extent… that the winemaking families fell to the lowest level of poverty and were forced to pawn or sell their household goods. Their exploitation culminated in vintners’ daughters succumbing to prostitution.” (Johnson, 1999).

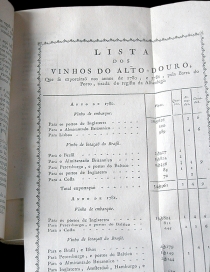

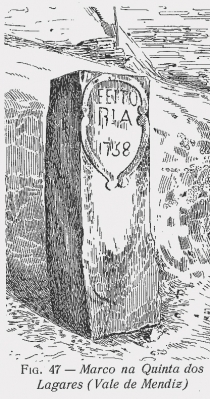

Financial constraints caused by having to rebuild Lisbon after the 1755 earthquake prompted the Marquis of Pombal to reform the Port wine regulations. For the first time in history, regulations were put in place which geographically demarcated a wine growing region (see graphic of a boundary stone. Fig.71). He also founded under Royal Charter the “Companhia Geral de Agricultura das Vinhas do Alto Douro”. This piece of legislation guaranteed traceable export records, and divided wines into the categoriesof vinho do ramo, which was exported to Brazil, and vinhos de feitoria, destined for the rich in Northern Europe, especially England (Johnson, 1999: 227). These measures made it possible to control quality and prices in conformity with free market principles, a system which is essentially still in place today. It is interesting to note that the grapevine varieties were not disclosed here, as was the case in Madeira, since they were a well kept secret of the feitorias (wine blending establishments) of the Douro. Export volumes reached their peak at the time of the Methuen Treaty of 1703 mentioned above. “Fine wine” (Port wine) became very popular in England, whilst the Pico wine from the Azores was held in high esteem by the Russian Court.

IN SPAIN

Rioja. Although one assumes that viticulture was practised before (Celtiberians) and during Roman times, the oldest known document referring to wine growing is dated AD 873 from the Notary Public of San Millán and deals with a donation to the monastery of San Andrés de Trepeana (Treviana). With the pilgrimage routes to Santiago de Compostela, some monasteries dedicated themselves to viticulture – ostensibly to produce sacramental wine. What is known is that the vineyards of Nájera belonged to the Millán monastery around 1024. In 1102 King Sancho I offically recognised the wines from Rioja, although it was not until 1352 (Peñin, 2008: 39) that the Rioja was designated a wine growing region.

In the Middle Ages, Logroño lay on the (French) pilgrim route and experienced economic prosperity with the help of the monasteries (Fernando Andrés 2000: 83 ff.). Rioja has a detailed history. In 1574, a Royal Decree banned the importation of wines from other regions. In 1770, Carignan was prohibited because of the bad quality of the wines this variety produced in the fertile soils of the region. It was in 1650 that the first mention was made of ensuring that only wines from this region bore the name Rioja.

It was not until the industrial boom in the 19th century that Rioja experienced a revival, thanks to several large wineries, located initially in Haro. Logroño soon followed with other wineries. Wine was shipped through the port of Bilbao. Marqués de Riscal was one of the first really big wineries. Since the American plague only came to Rioja much later than it did to France, the export to Bordeaux on account of the similarity between the wines gave a boost to the Rioja wine industry. It was only at the end of the 19th century that Rioja became the most important wine exporter internationally, a position which it still enjoys today (See Fig. 94). Its traditional standard cultivars are Garnacha Tinta and Tempranillo.

Cantabria, largely uninfluenced by the Arab conquests, was able to develop its own culture. Important medieval iconography was found in the San Beato de Liébana monastery depicting grape harvests dating back to AD 772. Because religious Christian documents fell victim to the missionary zeal of fundamentalist rulers and their armies, these illustrations from such an early Christian period are particularly rare on the Iberian Peninsula.They have survived to this day in various places because medieval monks made copies of them (See Fig. 73). They are currently housed in the Santa Cruz Library, University of Valladolid).

Castile and Leon. There are depictions of wine on the 12th century Romanesque frescoes in the Royal Pantheon of the Basilica of San Isidoro in Leon (See Fig. 72). Verdejo wine from Medina del Campo was already known at the time. Peñin (2009: 184) writes that because it was situated on the pilgrimage route just before Santiago, it already had strongtiestoviticultureinthe10thcentury,andthisiswhere Church viticulture began. In the 13th century, the banks of the Ribera del Duero (Douro River) were more intensively cultivated than they are today, and vines were cultivated here at altitudes of up to 1,000 metres. Viticulture is said to have been practised in Cigales since Roman times.

During the Middle Ages, there were numerous castles and monasteries, particularly Cistercian ones, and monks who originally hailed from the Benedictine Abbey of Cluny in Burgundy. Thus it was that the Clarets of Cigales took pride of place at the Royal table. At the beginning of the 14th century, Alfonso XII transferred the Toro vineyards to the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela in order to take care of the wine requirements of the diocese. The Edict of Oviedo (1274) called for traders to purchase their wine from Toro. In the 13th century (Huetz, 2000: 12) other monasteries such as Arbes, Valdedíos, and Meira also received bequests of vineyards in Toro. In 1437 a law was passed which permitted nurses to obtain wine in Toro. In the 15th and 16th centuries, Gabriel Alonso de Herrera knew of many important wine growing regions, such as Toro, Valladolid, Bierzo, Aranda del Duero, Tordesillas and others. The marriage of King Henry VIII to Catherine of Aragon at the beginning of the 16th century ushered in new trade relations with England. Alain Huetz de Lemps (in Actas del I Encuentro de Historiadores 2000: 11) mentioned that in the 18th century white wine cultivation on the Spanish Douro was substantially greater than it is today. The white wine of the Tierra de Medina at the time comprised 26,000 hectares compared to the mere 9,000 hectares of Rueda today. Rueda was once criss‑crossed with a labyrinth of wine cellars. In the area around Burgos annual production of Rosé (Claret) was over 50,000 hl during the 16th century. Production from the red wine region of Toro was greater, although both red and white wines had yields of less than 1,000 l/ha. During this period many vineyards were close to or in the cities themselves. At that time, the Verdejo grape variety was already the subject of much discussion, although the white wines were named “vino de Madrigal” after the birthplace of the Catholic Queen Isabel. It was also the wine of choice at the courts of kings.

The American plague had a drastic effect on wine growing in this region. After such a short‑lived experience of great prosperity as a result of the huge increase in demand due to France succumbing to grape phylloxera, at the beginning of the 19th century, the vineyards had to be pulled up here too. New vineyards were planted primarily with new French hybrids, and the region’s wines experienced a sharp drop in quality. Cultivation in Rueda returned to a little over 1,000 hectares.

After the Reconquista, Valencia was able to reclaim its long winemaking tradition from pre‑Roman and Roman times, which was not completely lost during the

Arab occupation. In the Middle Ages Jaume Roig (1460) describes the Monastrell, Bobal, Ferrandella and Negrella (Garnacha) varieties, which were grown in the hills of Valencia and Cuenca 600‑1000 metres above sea level. Innovations during this period included distillation to produce Aguardiente using a new aparatus called an alambique [alembic]. The making of so‑called “Greek wines” (wines fortified with aromatic herbs) using the Fondillón of Alicante was a timely response to the Turkish invasion of the Greek islands, which brought with it religiously‑motivated restrictions on the original local Greek wine. Ramón Muntaner, Señor de Xirivella, reported that the Malvasia grape from Greece was introduced to Valencia (Juan Piqueras Haba, in Actas del I Encuentro de Historiadores 2000).

Jerez de la Frontera. Foreign traders (Tartessians, Phoenicians, Greeks, Romans) became interested in the wines in the South of Seville early on in history. Jerez wines first came to England when Henry VIII married his first wife, Catherine of Aragon. In Henry IV (1608), Shakespeare has Falstaff pay grandiose tribute to Sherez (as Xerez was known to the English at the time). During the reign of Edward VII (England) the first commercial contracts were concluded with respect to Sherez wines. The marriage of Henry VIII’s daughter, Mary I to Philip II of Spain saw a fresh short‑term recovery for Sherez, although trade relations became somewhat murky when her half‑sister Elizabeth seized power in England. When voyages to America flourished in the 16th century, Cadiz was the largest export port in Spain, where international trading houses established themselves; initially, the French (mostly from Limoges), then the Italians, and members of the Hanseatic League, so that one could almost speak of a truly foreign colony (Canin 2008: 237). During this time, Cadiz became one of the richest cities in Spain, and was often the target of large‑scale piracy, including the activities of English corsairs. This was how Drake is said to have captured 3,000 barriques of “sack” (sherry) in 1587.

Later, Puerto de Santa Maria (Jerez de la Frontera) also gained in importance because of its proximity to areas where wine was grown specifically for export. The wines had an alcohol content of 12‑16°, were white, and made from the Torrontés, Fergusano, and Albillo grape varieties. The first major wineries were owned by British families, who appreciated this wine because it could be stored for long periods.

From the 18th century onwards, the flavour of the wine changed to the predominant one it still has today, with residual sugar and an alcohol content of 18‑20° similar to Port and Madeira wines. The combined storage capacity in 1796 of the Haurie, Gordon, Beigbeder, Lancaster and Harkon wine cellars is said to have accounted for 1.5 million arrobas [One arroba was equal to 25 pounds (11.5 kg) in Spain, and 32 pounds (14.7 kg) in Portugal, although the modern equivalent has been standardised to 15 kg.] (Cañin, 2008: 242 ff). Later, it was Pedro Domecq (1822 acquisition of Haurie), and others such as Barbadillo, Conde de Burgos, Fernando Gonzalves, William Garvey (Ireland), Duff Gordon and Osborne, González Byass, and many others, who entered the trade.

Sherry had a special place in Victorian England (Katharina Groëssl, Tipos de sherry en época Victoriana, in Actas del I Encuentro de Historiadores 2000: 113). The following categories come from 1858: Sherry Wine, Very Old Wine, Los Royal Pale, Los vinos de marca Romana (according to the Gonzáles Byass archives). By 1866, Sherry wines had become particularly well regarded and were now loosely classified into the different colour types of Pale, Golden and Brown, and were labelled as such. Subsequently, they were formally classified as Amontillado, Pajarete, Pedro Ximénez and Very Choice Wines. The call for a legal specification of the wine’s region of origin, the grape varieties used, and the type of wine to indicate its “mark of origin” was first made at the time of the American plague outbreaks in the second half of the 19th century.

In Catalonia there are documents with references to the Great Plague of 1348, after which vineyards became overgrown (Xavier Cidevila, I Temporal La viticulture y el Comercio en la Catalunya, 2000: 207 ff.). Numerous other documents (feudal bonds and notarial deeds) provide evidence of viticulture as far back as the 10th century. Many new vineyards were planted in the 13th and 14th centuries. Most of the vineyard plots were small. Feudal lords might award as much as one‑quarter of the harvest to their tenants, but the winegrowers, in turn, were obligated to prune the vines and gather the manorial harvest. The wine thus produced was traded. Documents from 1305 onwards show that wine was exported to Mallorca, and even to North Africa.

The acquisition of Portugal by the Spanish Hapsburgs signalled the end of Iberian supremacy in the wine trade. With its trading companies in the East and the West, and supported by commercially experienced Sephardic Jews who had settled there after the pogroms in Iberia, and the French Huguenots, who preferred the tolerant climate of the Netherlands to that of their mother country, Amsterdam needed a true reformation of the “geography of beverages” (Gaspar Martins Pereira: O Comércio do Vinho na Época Moderna, Almendralejo 2011). A fashion for fortified and sweet wines emerged in the 16th and 17th centuries which ushered in a period of “calibrated”, or treated, wines. The wine merchants’ chief interest was to enhance and enrich cheap base wines. Not only the Douro region, but also other quality wine regions in Iberia suffered as a result.

Finally, in the 17th century, things came to a head over disputes on economic policy as it related to the wine trade. France was severely disadvantaged by the import embargo imposed during the Franco‑Dutch War of 1672‑1678. The Methuen Treaty of 1703 between Portugal and England in conjunction with the Spanish War of Succession of 1702‑ 1714 served to strengthen the position of Portuguese wine exports to the extent that two Portuguese wines dominated trade networks from London to Ohio: Port and Madeira.

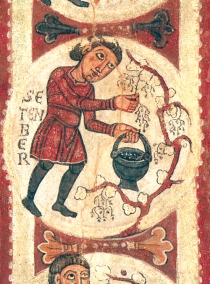

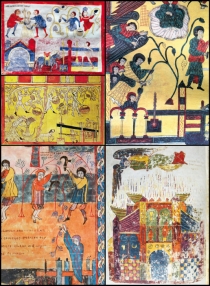

Fig. 63: The influence of the Church enhanced the value of the grape and wine (sacramental wine, The Last Supper, etc.). During the Reconquista and amongst the military Orders of the Crusades wine was considered as compensation for monastic celibacy, apart from its symbolic significance as the Blood of Jesus. (Hans Jörg Böhm Collection).

Fig. 63: The influence of the Church enhanced the value of the grape and wine (sacramental wine, The Last Supper, etc.). During the Reconquista and amongst the military Orders of the Crusades wine was considered as compensation for monastic celibacy, apart from its symbolic significance as the Blood of Jesus. (Hans Jörg Böhm Collection).

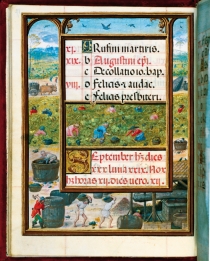

Fig. 64: In the late medieval Livro de Horas de D. Manuel I (“Book of Hours” – Manuel I, King of Portugal and the Algarves) the vintner’s seasons are depicted in four iconographic panels. Autumn is shown here as part of the vegetative cycle. This portrayal of 16th century wine growing techniques reflects the high professional standard viticulture had already achieved in Portugal. Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga[National Museum of Ancient Art], Lisbon.

Fig. 64: In the late medieval Livro de Horas de D. Manuel I (“Book of Hours” – Manuel I, King of Portugal and the Algarves) the vintner’s seasons are depicted in four iconographic panels. Autumn is shown here as part of the vegetative cycle. This portrayal of 16th century wine growing techniques reflects the high professional standard viticulture had already achieved in Portugal. Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga[National Museum of Ancient Art], Lisbon.

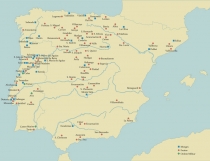

Fig. 66: Iberian monasteries in the Late Middle Ages.

One of the objectives of the Reconquista was to strengthen Christianity in the reconquered regions. The Cistercian Order in particular, as well as the Knights of St. Benedict of Aviz

and the Order of Christ, helped the Christian population to survive by undertaking specific agricultural research activities. Monastery from the Late Middle Ages.

Fig. 66: Iberian monasteries in the Late Middle Ages.

One of the objectives of the Reconquista was to strengthen Christianity in the reconquered regions. The Cistercian Order in particular, as well as the Knights of St. Benedict of Aviz

and the Order of Christ, helped the Christian population to survive by undertaking specific agricultural research activities. Monastery from the Late Middle Ages.

Fig 67: The Marquês de Pombal felt compelled to find new sources of funds to finance the reconstruction of Lisbon after the 1755 earthquake. He founded the Companhia Geral da Agricultura das Vinhas do Alto Douro, under Royal Charter, effectively granting protection to Port wine. He also established a quality-orientated classification of geographical plots in the Douro Valley, which meant that a terroir-based regulation on wine quality was legislated for the first time in world history.It was thus that English dominance over the Portuguese wine trade was broken for the benefit of the Portuguese state coffers.

Fig 67: The Marquês de Pombal felt compelled to find new sources of funds to finance the reconstruction of Lisbon after the 1755 earthquake. He founded the Companhia Geral da Agricultura das Vinhas do Alto Douro, under Royal Charter, effectively granting protection to Port wine. He also established a quality-orientated classification of geographical plots in the Douro Valley, which meant that a terroir-based regulation on wine quality was legislated for the first time in world history.It was thus that English dominance over the Portuguese wine trade was broken for the benefit of the Portuguese state coffers.

Fig. 73 a, b, c, d, e: Various icons. While most of the iconographic works from the early days of Antiquity were destroyed by the Saracens and later by iconoclasts of the Inquisition, some significant illustrations of the grape harvest dating to 772 BC have been found in North Cantabria at the Monastery of San Beato de Liébana. Facsimiles of these and other icons with a viticultural theme are housed in the historical library at the University of Valladolid.

Fig. 73 a, b, c, d, e: Various icons. While most of the iconographic works from the early days of Antiquity were destroyed by the Saracens and later by iconoclasts of the Inquisition, some significant illustrations of the grape harvest dating to 772 BC have been found in North Cantabria at the Monastery of San Beato de Liébana. Facsimiles of these and other icons with a viticultural theme are housed in the historical library at the University of Valladolid.

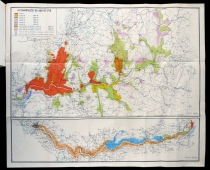

Fig. 74: Map belonging to Sir Francis Drake

(San Fernando Library). After the explusion of the Narid

(a Saracen people) from Andalusia, the port of Cadiz became one of the most important trading centres near the Straits of Gibraltar. In 1587, Drake attacked the harbour, and captured amongst other things 3,000 barrels of “sack” (Sherry wine).

Fig. 74: Map belonging to Sir Francis Drake

(San Fernando Library). After the explusion of the Narid

(a Saracen people) from Andalusia, the port of Cadiz became one of the most important trading centres near the Straits of Gibraltar. In 1587, Drake attacked the harbour, and captured amongst other things 3,000 barrels of “sack” (Sherry wine).