The Presence of Wild Vines during the Ice Age in Iberia

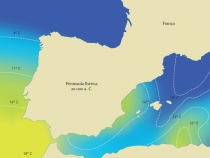

During the glaciation 20,000 years ago, the sea was, because of the land‑based ice, up to 110 metres deeper than is the case today. The mountain ranges of the Iberian Peninsula such as the Pyrenees, with the Cantabrian mountains, the mountainous region of the Sierra Nevada as far as Murcia, as well as the Serra da Estrela as far as Valencia show evidence of glaciation and the climate in the interior of the Iberian Peninsula had continental features, which were characterised, in contrast to the coastal regions, by stable temperature variations. Because of prevailing water temperatures, the coastal regions of the Mediterranean Sea and the Southern coastal stretches of the Atlantic were characterised by a climate favourable for thermophilic vegetation. Nevertheless, it should be mentioned that the temperatures of the Mediterranean off the Spanish coast were ten degrees colder than today’s 22° C. In Marseille, the temperature in summer was only 10° C, which was made colder by the cold winds that blew from the glacial Northern Europe southwards, using the same corridor West of the Alps as today’s Mistral. By contrast, the temperatures near Libya, Egypt and the East Mediterranean countries were higher than 20° C even during the glacial period (compared to today’s 26° C). The Eastern regions found themselves subjected to the highs of the anticyclonic current of the Eurasian cold, whilst the West coast, because of the Southern arm of the polar jet stream, were fed moisture from the Atlantic (Hayes, Kucera, et al., 2004; Kucera, 2008).

Historic Migration

European tree varieties in Central Europe North of the Pyrenees, Alps and in the Eastern Caucasus were displaced and because of the unfavourable climatic conditions could only survive in refugia further South. The precise locations of the glacial refugia are not always that clear. The same applies to Vitis. Based on discoveries of plant remains in glacial period sediment, however, the Mediterranean would appear to have been a valid refuge area for most of today’s central European tree varieties such as the Common Beech (Fagus silvatica). Presumably, some varieties could have survived on the South‑east rim of the Alps and in the Balkans (cf. Walter and Straka, 1970: 234 ff.).

Because the determination of glacial period refugia has already encountered some difficulties and uncertainties, the reconstruction of migratory routes of individual varieties should also be approached with a certain amount of caution. For Europe, it is assumed that the migratory process occurred primarily along the large valleys. It would have been possible to circumvent the Alps via the Belfort Gap, linking the Rhine and the Rhône, and via the Moravian Gate to the Danube, Vltava (Moldau), and Elbe basins. Indications are that this must have been the case with the Vitis silvestris populations found in the modern era on their return migration from their regions of refuge. The situation in Iberia was quite different in that the Peninsula was isolated and in principle, migration took place within the Peninsula only.

It may point to a variation in effects between Europe on the one hand and North America and East Asia on the other. Whilst in Europe, the West‑East gradient of the Pyrenees, the Alps, and the Tatra Mountains precludes a southwardly evasion by the vegetation of the inland ice mass, this occurred easily in the geographically more expansive regions of North America and East Asia. Consequently, Europe suffered a decimation of its flora, which one can assume would have entailed the loss of many varieties with each successive glaciation. Similarly, a sharper division occurred between the Mediterranean and the Central European hinterland. One proof of this is provided by a comparison with the western regions of North America, where a higher concentration of native species than in Central Europe is prevalent, to which the genera Pinus, Ginkgo, and Magnolia, as well 35 Vitis genera testify. Europe, on the other hand, has only the genus Vitis vinifera L. It can also be inferred that repopulation of areas previously affected by transmigration occurred much more quickly at the beginning of the Holocene epoch in North America than it did in Europe (Richter, 1997).

Vegetation and Spread of Vitis silvestris in the Southern Europe of the Last Ice Age

The climatic fluctuations resulted in certain species being displaced, whilst allowing others to propagate. The descriptions of vegetation cover of the Mediterranean region during glaciations, however, vary from author to author, because of the different pollen analysis methods employed (cf. Strasbourg, 2008 and Menéndez & Florschütz, 1964). One explanation for the occurrence of different dominant vegetation types can be traced to minor climatic instabilities. Therefore it can be assumed that trees and shrubs only occurred in suitable areas in the often forest‑free steppes in the Mediterranean and sub‑Mediterranean zones of Southern Europe. These habitats, often at submontane altitudes and in the humid river valleys, provided refuge for most of today’s European forests, amongst which Vitis silvestris was able to survive (See Fig. 107). The remaining zones of the low lying Estremadura, Algarve and Alentejo, maritime Portugal as far as the Minho, parts of the Douro valley, and possibly Rioja with the Ebro valley, can be grouped with these (submontane) habitats, which were covered with open steppe‑like vegetation, sporadic coniferous forests in Northern and central Iberia, as well as alternatively, closed mixed forests and deciduous forests in the South and along the Atlantic and Mediterranean littorals. Likewise, because of pollen discoveries, it can be said that grassland vegetation was often characterised by an Artemisia‑ Chenopodiaceae combination, as was the case in the Iberian region of Padul, Granada province, Southern Spain some 750 metres above sea level (Menéndez & Florschütz, 1964).

Meanwhile, in the post glaciation warm period, Vitis vinifera silvestris wandered back westwards and northwards around 7,000 years ago and arrived in Iberia via the Rhône, Rhine and Danube river valleys.

Fig. 106: Landscape and the spread of vegetation during the Würm/Weichsel glaciation. In this glacial period, the grapevine was pushed back into the ice-free Mediterranean countries and the Orient.The probable refugia during this glaciation, according to Levadoux, 1956, are indicated here by a red line.

Fig. 106: Landscape and the spread of vegetation during the Würm/Weichsel glaciation. In this glacial period, the grapevine was pushed back into the ice-free Mediterranean countries and the Orient.The probable refugia during this glaciation, according to Levadoux, 1956, are indicated here by a red line.